On May 10, 1842, President John Tyler announced the termination of military action in the territory of Florida, bringing an official end to the Second Seminole War. This did not end hostilities, and tensions remained, with some three thousand Seminoles having been captured and forced from their homes at gunpoint and removed from Florida. While the United States hoped that the end of the war would convince the roughly 240 remaining Seminoles to abandon their homes and join their kinfolk in the West, this did not happen.

Further, white settlers had also lost homes and livelihoods in bloody skirmishes, and the threat and reality of continuing hostilities discouraged them from moving to Florida. To colonize the land, an offer was made that was too tempting to resist for many Americans.

The Contents of the Armed Occupation Act

The offer that was presented by Congress was the Florida Armed Occupation Act of 1842. This granted 160 acres of unsettled land to any head of a family who met the conditions of the act. The homeowner could gain up to 200,000 acres of land if he had multiple claims. The conditions of this Act were:

- The claimant must be white, male, and a resident of Florida who did not yet have 160 acres of land in Florida when asking for the permit.

- He must file for the permit at the Lands Office.

- He or his heirs had to live on the land for five consecutive years on the land grant.

- He had to clear, enclose, and cultivate at least 5 acres of the land during the first year.

- He had to build a house on the land within the first year.

- He could not place a claim on any land that was within two miles of a garrisoned military post.

Further, they were expected to become a militia, able to be called upon if needed to handle the threat of the remaining Seminole Indians.

Some of these conditions were difficult for the settlers. Naturally, most settlers would want to live as close as possible to US Army Forts for protection, but as the purpose of the act was to colonize as much land as possible, the prohibition against placing settlements within two miles was included.

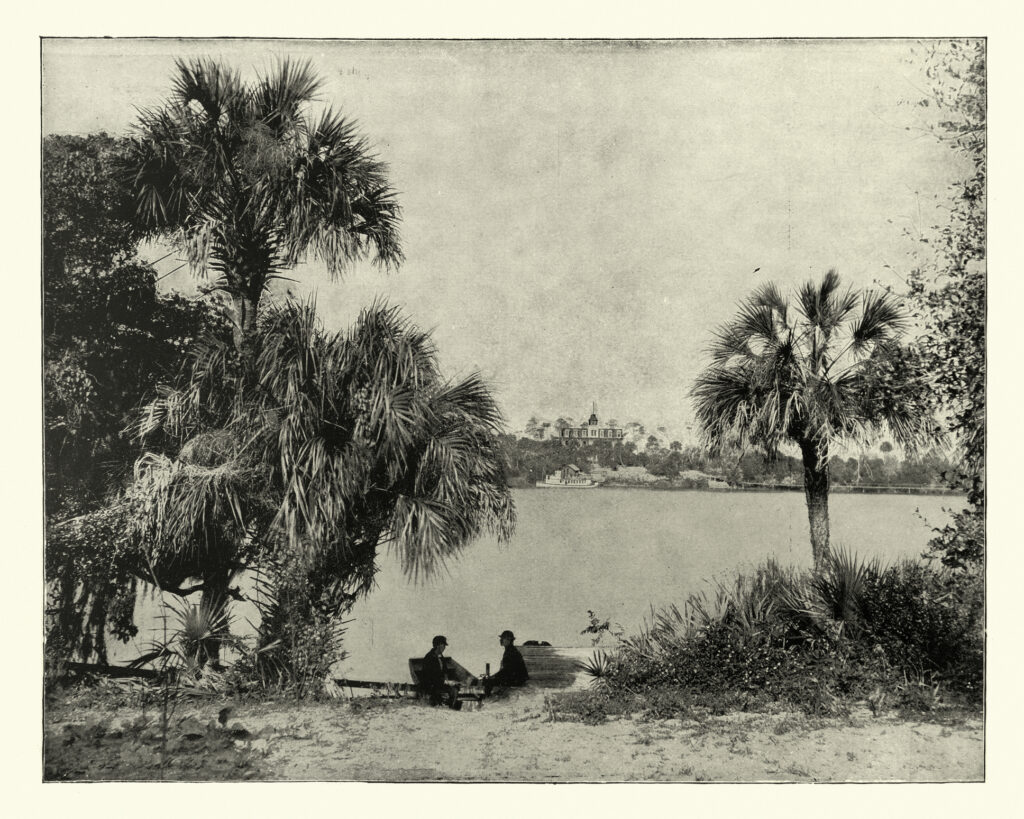

The land which was available came from present-day Gainesville to St. Augustine and the Peace River, though the land south of the Peace River was out of bounds as it was where the Indian reservation section was.

The Formation of the Armed Occupation Act

The Armed Occupation Act was not created in a day. In fact, the first suggestion of it was when Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri introduced it in 1840. He presented a speech in favor of the proposed Bill. Despite the speech, there was determined opposition by Southerners, including Senators from North Carolina, Kentucky, and South Carolina, and the measure was defeated.

When President John Tyler announced the termination of the Second Seminole War in May of 1842, he claimed there were approximately 80 adult male Seminoles left in Florida. He expected it would be easy to convince them to migrate to Oklahoma and hoped that the settlers could move to Florida and be provided with food for one year.

While a trickle of settlers began even before that announcement, still there was pushback. The delegate to Congress David Levy of Florida was not enamored of Tyler’s message. He claimed the expensive seven-year war was not yet safe, as there was still a great deal of land in Seminole hands. Further, the Secretary of War, John C. Spencer, advocated the use of armed families, who would be provided provisions for one year, and that arms and ammunition would be loaned to these pioneers. Levy declared it foolish to declare the war at an end when the raids were still happening.

At this point in June 1842, Thomas Hart Benton re-introduced the Armed Occupation Act of two years prior with some modifications to allow for the arms and ammunition to be provided for the first year’s residence, but again, the opposition was strong. While it cleared Benton’s Committee of Military Affairs, the Senate defeated the amendment for arming the settlers. The bill, minus the amendment, passed the Senate by a vote of 24 to 16, with most of the support coming from the South and the West.

When the bill went to the House, it was passed 82 to 50, but the section dealing with free rations and a loan of weapons had been removed. Major opponents to the bill included John Quincy Adams from Massachusetts and William Johnson from Maryland, but David Levy won the day, and the act was signed on August 4, 1842.

Problems and Communications Gaps

Once the act was passed, implementation began. This came with its own series of issues: both due to a lack of communication with the Seminole Indians, and with the influx of claims.

Overlap of Communications

Even though the act was signed in August, most settlers could not take advantage of it right away. Nobody had bothered to tell the Seminoles that the war was over, and so skirmishes continued. In one case, an entire family was wiped out in September 1842. This lack of communication was understandable. While President Tyler had declared the war over in May, the troops were not informed that the hostilities had ended until August 14, 1842. If it took three months to notify US troops, it’s understood that there would be delays in passing the message to the Seminole.

Also, there were raids in the panhandle and Central Florida, but these were temporary and didn’t last long. Further, the ones who were raiding there were not the Seminole, but rather the Creeks of Alabama and Georgia.

By 1843, the Seminoles, who had been granted temporary use of land for hunting and farming, petitioned for permission to shoot ownerless cattle that were roaming the wild. The request was denied, but the act of them asking permission was a hint that there was no real danger at that time.

Issues with Implementation

There were some difficulties in implementing the act, however. First, settlers only had nine months after the act was enacted to take advantage of it. Nearly 1,200 homesteaders claimed 200,000 in the area, and some requests for permits were not within the requirements. For example, one person wanted 163.2 acres instead of 160 and had their request denied, while a woman with sons and slaves capable of bearing arms applied for land and was approved. Further, if a person passed away before the five-year period had expired, his heirs were allowed to continue the rights, and a person was not allowed to exchange land which was subject to flooding for higher land. Another limitation was that while a man was allowed to clear some land and use the logs for the construction of his home and fences, he could not sell the timber.

Because of these difficulties, 128 of these permits were annulled. At least 66 sites were abandoned by people who discovered they’d bitten off more than they could chew. There were some permits that got canceled because the land had already been claimed by others, and some were within two miles of a military post, or on coastal keys and islands that were reserved for the military.

What Successful Settlers Did

For those who succeeded in settling their land and claiming the acres, life was standard: they’d erect their homes near some source of water, building their double-pen log houses with detached kitchens and other buildings such as quarters, barns, and smokehouses. They’d grow gardens which were enclosed by fences made of sharpened split pickets meant to keep out wildlife. They’d have a small herd of cattle feeding in the forest, and sometimes even virtually wild hogs and chickens. Food was not a problem.

Armed Occupation Act: Success or Not?

Was the Armed Occupation Act a success or not? For the United States, mostly, but not entirely. While Commissioner Richard M. Young, who oversaw the operation, deemed it a success and the act enabled successful settlers to form pioneer communities that stretched from the Indian River to Tampa Bay, they were not able to form a band of hard-fighting farmers. Not only that, but inexperience caused many to bypass valuable agricultural lands, and most settlers stayed within the central belt. Very few traveled down to the very swampy Dade County.

Indirectly, though, the Act did result in the successful removal of most of the Seminole from Florida.