Fort King in Ocala was built in 1827 initially and was likely abandoned during the summer due to the influx of summer illnesses. This led to the cessation of war activities during the hotter months, which would resume during the following winter, despite the territorial governor preferring to continue the campaign throughout the year. It was during this time of abandonment, in May of 1836, that the Seminole burned Fort King to the ground. One year later, the US Army returned and rebuilt the Fort before starting “search and destroy” missions against the Seminoles. Because of this, we know that the blacksmith shop would likely have been associated with this second fort, built in or around 1837.

Finding The Blacksmith Shop

Building the blacksmith shop was a lengthy process that began with the archaeologists. The initial teams came to the Fort King site to begin the hunt for where the blacksmith shop was most likely to be located.

Shovel Tests and Grids

The first team began the prep work for finding the blacksmith’s shop in 2010. They employed shovel tests, which is a process that creates a series of test holes which are usually dug out by shovels to determine if the soil has anything of cultural value. Archaeologists sifted through the soil. With these shovel tests, they mapped the site and created a grid out of the discoveries.

Searching For Signs of the Shop

While most of the Fort King site has brought many artifacts from glass, bottles, lead shots, and military buttons, the archaeologists spent most of their time looking for nails, the key to finding where the blacksmith shop would be located. Many nails were found in the clay, possibly scattered when posts were pulled up from the ground. The size of the nails determined if a section was an interior or exterior wall.

In 1830, the production of machine-cut nails began, where there would be a sheet of nails that the builders would break off pieces of, but Fort King was in the middle of the wilderness, not close to the roads. They would be getting supplies in from Pensacola or from the St. John’s River, so they’d need to either make nails at the fort or repurpose other nails. Because of this, the blacksmith’s shop probably made more nails than anything else. The nails that were found were mostly rectangular with a rectangular head.

What the Dirt Says

Archaeologists can learn a great deal about history from the dirt itself. While digging, they discovered some dark grey sand which came from about the same time the houses currently on the property were lived in, probably from just before the 1960s or 1970s. Beneath that was yellow sand, which is most likely from the 1800s when the fort was occupied. Throughout that, and a bit deeper, was clay.

By eliminating spots where the dirt was compact and unnaturally dark, they were able to focus on the areas which were more consistent with the dig areas, and more likely to be part of the Blacksmith Shop’s location. Based upon the dirt, the clay, and the scattered debris, they were able to determine a 10’x10’ or 10’x12’ diagonal location where the blacksmith shop most likely was located.

Found in the Hunt

In the area where the blacksmith shop was discovered, they found other artifacts that helped piece history together. Based upon the many clay pipes found, it was decided the blacksmith was probably a heavy smoker, and other items helped them conclude that most likely, the blacksmith lived on site. They also discovered items like buckles that would go on backpacks.

Who Was the Blacksmith?

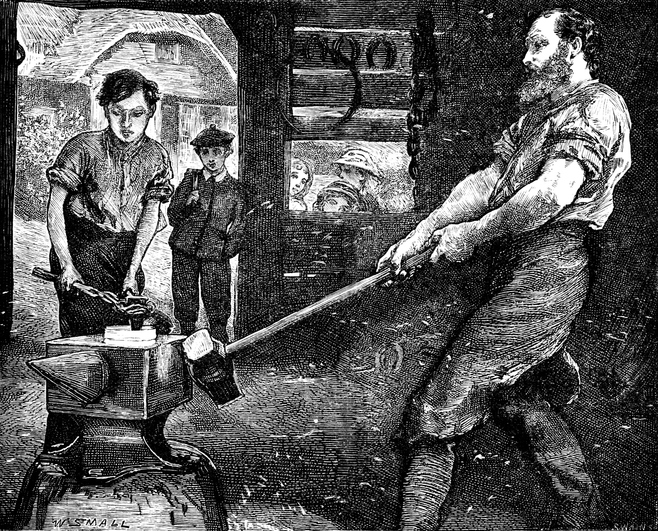

The blacksmith in the 1800s was essential to civilization, communities, and especially military forts. They were tradesmen and businessmen, utilizing a variety of large equipment to make a wide range of products.

The Training to Be a Blacksmith

It wasn’t easy to become a blacksmith, and the successful smith had to be more than just a craftsman. They went through a rigorous 7-year apprenticeship, being fed, and trained in return for assisting the master smith. Because of the demand for metalwork and the sheer amount of training that went into the craft, the blacksmith was a very respected individual. It became customary to pay the apprentice a small wage instead of housing them by the 1830s. The apprentice would begin at an early age and become a journeyman by the age of twenty-one.

What the Blacksmith Made

Of course, the blacksmith made nails. Before 1830, a smith could forge nails at a rate of one per minute, so nails were expensive. The machining process sped up production, which made them more easily obtained, but at least nobody was burning down homes just to get the nails!

The blacksmith at the fort would create all sorts of items: axe heads, horseshoes, nails, the steel for flint and steel, and of course their own tools of the trade, like a nail header. In the research to build the blacksmith shop, archaeologists discovered that the dragoons, who were the cavalry before the 1850s, would travel with their own farrier and forge, so the blacksmith at the fort might make fewer horseshoes than construction supplies. Artificers were listed with the military to fix wagons, do woodworking, and leatherworking, and while they could act as makeshift blacksmiths, they had many other duties to perform. A blacksmith would also help maintain the artillery. While the Dragoons would have their own farrier and anvil, the infantry would have to rely on a fort that had a blacksmith. Also, though the Indian Agency to the west most likely had its own blacksmith, having to transport goods from there to Fort King would put the supply chain at risk of attack by the Seminoles, so anything metallic for daily living at the fort, or the surrounding homes, would require the services of the blacksmith. Highly likely, they built trivets, buckles, hinges, and much more.

The Blacksmith of Fort King

Based on the artifacts found, it is likely the blacksmith at Fort King lived onsite. He was probably a civilian, due to the sheer number of years required to become a skilled blacksmith. He may have produced his own charcoal, would have been able to tell the temperature of a fire by color, and would have known how to run his business in a way that was profitable to him.

The Tools and the Workshop

The blacksmith’s shop, tools, and materials were essential to his trade. As everything was made for maximum efficiency and profit, the blacksmith had to be a very practical and savvy businessman.

The Workshop Setup

The blacksmith’s workshop was designed for practical use. The small one-room workshops were often made with few windows, as darkness made it easier to see the glow of the metal. There would be a forge, with a chimney and bellows on one side to help concentrate the fire’s heat. Nearby, the anvil would stand, ready for frequent use. The collection of scrap metal, coal fuel, and refuse would be on the walls and corners of the workshop, although some would keep the scrap and fuel outside of the workshops to prevent accidental fires and save space. Lastly, most blacksmith shops would have a waiting area, though in a military base, that wasn’t always the case.

Tools of the Blacksmith

Besides the forge, anvil, and bellows, the blacksmith used many tools: such as hammers, tongs, forms, wedges, chisels, and nail head forms. Many of these would be created by the blacksmith on site, and in fact, across the blacksmith’s career he might accumulate hundreds of different tools, often that were used to make one single item. What is more, the blacksmith’s tools were often very individualized, as they were made by themselves, for themselves.

The Materials Used

Before the 1830s, blacksmiths mostly used iron because it was cheap and easy to manipulate, however, after the invention of the steel plow in 1838, the use of steel became a more popular choice for blacksmiths. Oftentimes, the smith would purchase hoops and bars of metal. For example, in the 1830s, wrought iron cost six cents per pound, which made it a very cost-effective choice, while steel would cost closer to eighteen cents or even 25 cents per pound. The smith would further save money by recycling scraps instead of buying new metal.