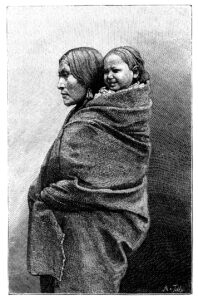

On May 28, 1830, the United States Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which began the forced relocation of thousands of Native Americans. While it freed more than 25 million acres of fertile, lucrative farmland to mostly white settlers in the Southeast, more than 46,000 Native Americans were forced to abandon their homes and relocate to Oklahoma. Along the way, many would die of starvation, disease, and exposure to extreme weather.

What led up to the Indian Removal Act of 1830?

By 1830, Anglo-Americans were seeking to expand into the Trans-Appalachian west in their search for more land and opportunities. The Americans saw three reasons to force the Native American population further west:

- They disliked that the Native Americans refused to assimilate into Anglo-American culture.

- American settlers continued to seek to expand westward and viewed the Native Americans as a hindrance to this effort.

- American settlers retained an animosity from earlier conflicts with the Native American tribes.

The main advocate for the removal of the Native Americans was Andrew Jackson, future President of the United States.

The Start: Voluntary Migration and Resistance

When Andrew Jackson became President, he made passing the Indian Removal Act a priority, and on May 28, 1830, it was passed. This was the first major departure from laws that protected the rights of the Native Americans. The act authorized the president to grant the tribes unsettled western prairie land in exchange for their desirable territories within state borders. This would require that the tribes be removed.

By the mid-1820s, it was clear that the American settlers would not tolerate any Native Americans, even those who were peaceful. President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act only allowed for the negotiation of the tribes east of the Mississippi on the basis of payment for the lands, there was difficulty. This happened when they tried to force the Indian’s compliance with its demand.

While some of the northern tribes peacefully resettled in the west which the American settlers considered undesirable, in the southeast, the members of what were considered the five “civilized” tribes refused to trade their cultivated lands for the strange, uncultivated land. These five tribes were the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole, Cherokee, and Creek. These tribes had homes, representative government, children in missionary schools, and trades other than farming.

Force and Resistance

Even before the Indian Removal Act of 1830, Native Americans were resistant to leaving their lands. This led to the First Seminole War, which lasted from 1817 through 1818. In this war, the Seminoles were helped by fugitive slaves who had been living with them for years.

After the Indian Removal Act, resistance continued amongst the Seminoles. While a small group was coerced into signing a removal treaty in 1833, the majority declared the treaty illegitimate and refused to leave. This led to the Second Seminole War, which began in 1835.

When the United States soldiers began to enforce the Indian Removal Act as mandatory migration, rather than voluntary,

A small group of Seminoles was coerced into signing a removal treaty in 1833, but the majority of the tribe declared the treaty illegitimate and refused to leave. The resulting struggle was the Second Seminole War, which lasted from 1835 to 1842.

When the U.S., enforcing the Removal Act, arrived, some of the Seminoles and Creeks in Alabama and Florida chose to hide in the swamps and avoid the forced removal. Some descendants of those who escaped have governments and reservations in Florida today.