From Invasions to October, 1821

By the time September 18, 1823 had arrived, the Seminole Indians had already been invaded three times, and had sustained extensive losses. After the first two invasions, the “Patriot War” of 1811-1813 and Andrew Jackson’s campaign in 1818, they were never the same. They were so harmed that Captain John R. Bell, US Army, and acting agent to the Seminoles said, “They had once been proud, numerous, and wealthy, possessing great numbers of cattle, horses, and slaves; they are now weak and poor, yet their native spirit is not so much broken as to humble them to the dust.”

“They had once been proud, numerous and wealthy, possessing great numbers of cattle, horses, and slaves; they are now weak and poor, yet their native spirit is not so much broken as to humble them to dust.”

Captain John R. Bell, US Army, Acting Agent to the Seminoles

When the Seminoles heard of the appointment of Andrew Jackson, their old conqueror, as governor to the new territory on March 10, 1821, it was bad news. They tried to find out what lay in store for them. Several times, some chiefs went to St. Augustine to make inquiry, but were not able to learn much. Then Micanopy, head chief of a number of their bands, arranged with two Americans: Horatio S. Dexter and Edmund M. Wanton, to negotiate a treaty for his people. This was close to July 17, 1821. This was also the date Andrew Jackson arrived and took formal possession of Pensacola. One of the first things Jackson did was sieze these two agents. While no harm came to either Dexter or Wanton, a treaty was not achieved.

On September 28, 1821, Secretary Calhoun appointed Captain Bell as acting agent to the Seminoles. At this point, Jackson was superintendent, Bell acting agent, and Penieres subagent. With this settled, it would have been possible for the Seminoles to find out what was in store for them, however it was not to be. On October 6, Andrew Jackson left for the Hermitage and never returned to Florida. Penieres died of yellow fever at the same time and Captain Bell was charged with conduct unbecoming of an officer and was suspended from his duties. The Indians remained uninformed.

Governor DuVal’s Entrance

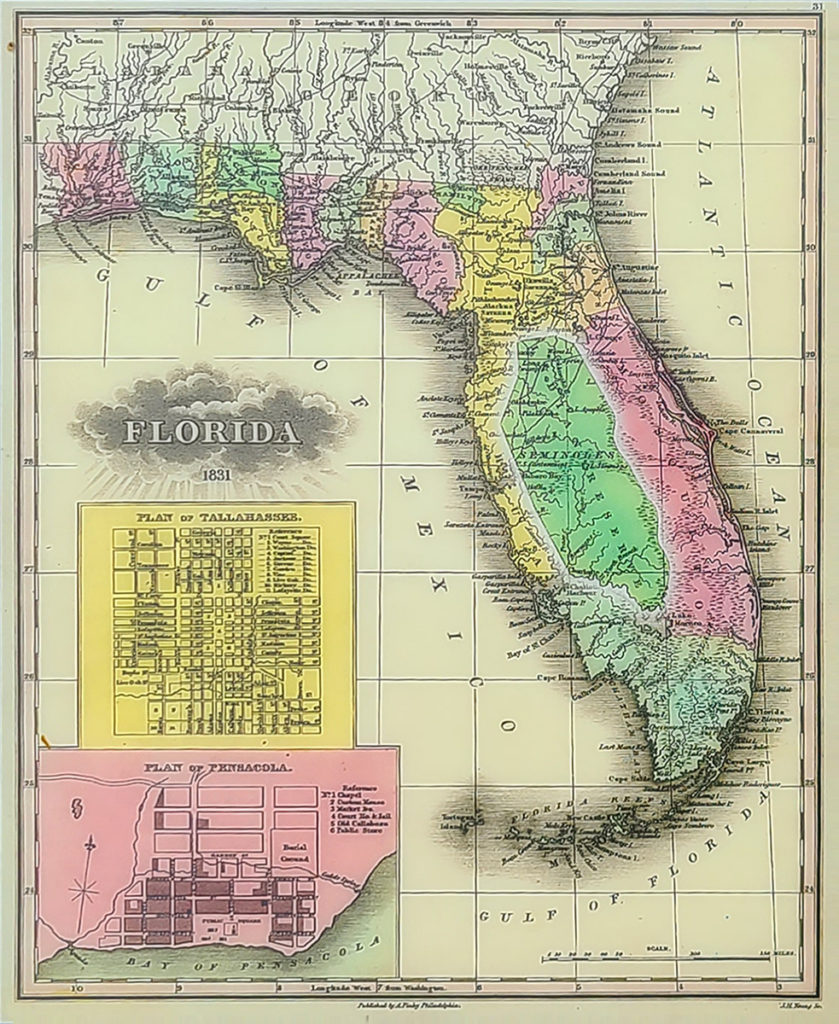

The Americans now faced a choice: concentrate the Indians somewhere in Florida or remove them altogether. While Governor Jackson preferred to remove them from the peninsula, he saw that it wasn’t obtainable at that moment. They decided to concentrate them along the Apalachicola River close to the Georgia and Alabama boundaries. The choice was made to cut them off from the ocean so that they would have to pass through white lands in order to get foreign aid.

Towards the end of 1821, the Secretary of War stated that the administration would not try to force the natives out unless Congress took the initiative and authorized the action and funded it. Meanwhile, Governor Jackson left and his duties were divided between two acting governors: William Worthington for East Florida and George Walton for West Florida. Peter Pelham replaced the late Penieres as subagent on October 29, 1821. Then on April 17, 1822, William Pope DuVal succeeded Jackson as the Governor of the Territory of Florida. Three weeks later, Major Gad Humphreys of New York was appointed Indian agent. Again, the Seminoles had hopes to learn their fate.

Governor DuVal found the Indians understandably uneasy. Floods had ruined their crops, some were starving. They were digging up miles of the country for “briar” root to avoid starvation. They were not willing to make improvements on the land because they expected the white settlers to confiscate it. On July 29, 1822 he made an attempt to help by issuing a proclamation to prevent people from settling near an Indian town and to prevent trade with the Indians. This wasn’t popular with his own people and couldn’t be enforced. Frictions between the two cultures increased, including border incidents and a couple of murders.

Through February 1823

The need to resolve the problem was fierce in late 1822. A council with the Indians was set to be held on November 20th, which was expected to produce an agreement, but before it could take place several things happened. Peter Pelham, the subagent, took ill and had to move north. Then in late September 1822, Governor DuVal abruptly left for Kentucky and Agent Humphreys didn’t appear in Florida. There was nobody left to negotiate. Acting Governor George Walton was left in a state of panic, especially considering a terrible epidemic of yellow fever was running rampant in Pensacola. He had not been briefed, nor did he have presents and food needed for a pow-wow. Meantwhile, the Indians had already been notified.

Acting Governor George Walton was left in a state of panic, especially considering a terrible epidemic of yellow fever was running rampant in Pensacola.

When the Seminoles arrived at the rendezvous on the 20th, there were no preparations to receive them, no agents. After three days they left, justifiably annoyed. Three weeks later, Thomas Wright, a paymaster in the US Army reached St. Marks. He called the nearby chiefs together and explained the embarrassment. The Seminole were good-natured about it and they agreed to remain calm until a permanent arrangement was made.

By March, 1823, Governor DuVal returned to Florida, blaming everyone but himself for the confusion. Meanwhile, in Washington the issue was under discussion. President Monroe even referred to it in his annual message. The House of Representatives established a temporary committee to report on the situation. The head of this committee, Thomas Metcalfe of Kentucky, obtained information and then on February 21, 1823 gave his report to the House. The committee decided that the Indians must be accorded the privileges of citizens of the United States. They gave each Seminole family a grant of land. The thought was that this would break up the tribal bond and instead put in private enterprise and integrate the natives with the Americans. This didn’t work out.

The Negotiations Begin

On June 30, 1823, Governor DuVal was instructed to make himself part of the commission. Along with the now-commissioned James Gadsden of South Carolina and Bernardo Segul of Florida, a summons to talk with the tribes was issued. Gadsden took a hard tone with the summons, informing the Seminole that “those tribes who neglect the invitation, or obstinately refuse to attend, will be considered as embraced within the compact formed, and forced to comply with its provisions.”

The council was set for the north bank of Moultrie Creek, about five miles south of St. Augustine. The American detachment would have a very short trip, while the Seminole bands would have to travel 250 miles to get there. Approximately 425 natives attended the talks. The Florida Indians did not constitute a cohesive society. The only thing that they shared was the Creek culture. They spoke two different languages: Muskogee and Hitchiti, as well as various dialects of these. And they did not arrive as a body, but rather as individual tribes.

The three major groupings were called Mikasuky, Tallahassee, and Seminole. In the article, the term “Seminole” is applied to almost all of the Florida Indians. For purposes of negotiation, the many bands needed a head chief. They foregathered a mile and a half short of the treaty ground and chose Neamathla, head chief of the Mikasukies. He was respected by both Americans and the natives, and in fact, Governor DuVal referred to him as the most remarkable savage he had ever seen. Because of this pre-meeting, the negotiations for the treaty started a day later than planned.

Two weeks of negotiations happened in the “bark house.” James Gadsden opened the negotiating with the same stern line he had employed with the summons. He implied that the Seminoles had better agree to their terms or take the consequences.

The Treaty is Formed, and What It Agreed On

Two days later, Neamathla replied. By September 10th, Neamathla’s speech changed. His people did not want to go to the reservation to the south. He stated, “We are poor and needy; we do not come here to murmur or complain;…we rely on your justice and humanity; we hope you will not send us south, to a country where neither the hickory nut, the acorn, nor the persimmon grows…For me, I am old and poor; too poor to move from my village to the south. I am attached to the spot improved by my own labor, and cannot believe that my friends will drive me from it.”

“We are poor and needy; we do not come here to murmur or complain;…we rely on your justice and humanity; we hope you will not send us south, to a country where neither the hickory nut, the acorn, nor the persimmon grows…For me, I am old and poor; too poor to move from my village to the south. I am attached to the spot improved by my own labor, and cannot believe that my friends will drive me from it.”

Neamathla, head chief of the Mikasukies

By the time the negotiations had ended, the Seminole were not forced to move south. The document which was signed stated that the Florida Indians surrendered all claim to the “whole territory of Florida” except for the district on the accompanying map. Their reservation was enlarged to include about 4,032,940 acres. It also included that the boundaries could be extended to the north if the reservation did not include enough tillable land. Two of these extensions were made in February and December of 1825.

In return, the United States obligated itself to protect the Indians as long as they obeyed the law, supply them with $6,000 worth of agricultural equipment and livestock on the reservation, pay $5,000 a year for twenty years. They also had to keep white men out of the reservation except those authorized to be there, provide the natives who were forced to move with meat, corn, and salt for one year, and pay up to $4,500 for improvements which the Indians were forced to abandon in the move. They had to provide up to $2,000 for transportation costs, and maintain an agent, subagent, and interpreter in the reservation. Finally, they were to pay $1,000 a year for 20 years to maintain a school on the reservation and $1,000 a year to maintain a blacksmith and gunsmith on the reservation.

The Indians were also required to prevent the concentration of runaway slaves in their midst. Their boundaries were nowhere near the coast…separated by at least 20 miles, which cut them off from intercourse with Cuba. Nor did the Treaty mention a duration.

Terms of the treaty were not fully upheld on either side, and this led to the Second Seminole War in 1835.